On Goblins

A recent BlueSky thread from Idle Cartulery has me thinking about what makes for good goblins in a TTRPG, and I’ve been thinking about it enough today it felt worth making a post to put down how I feel about them.

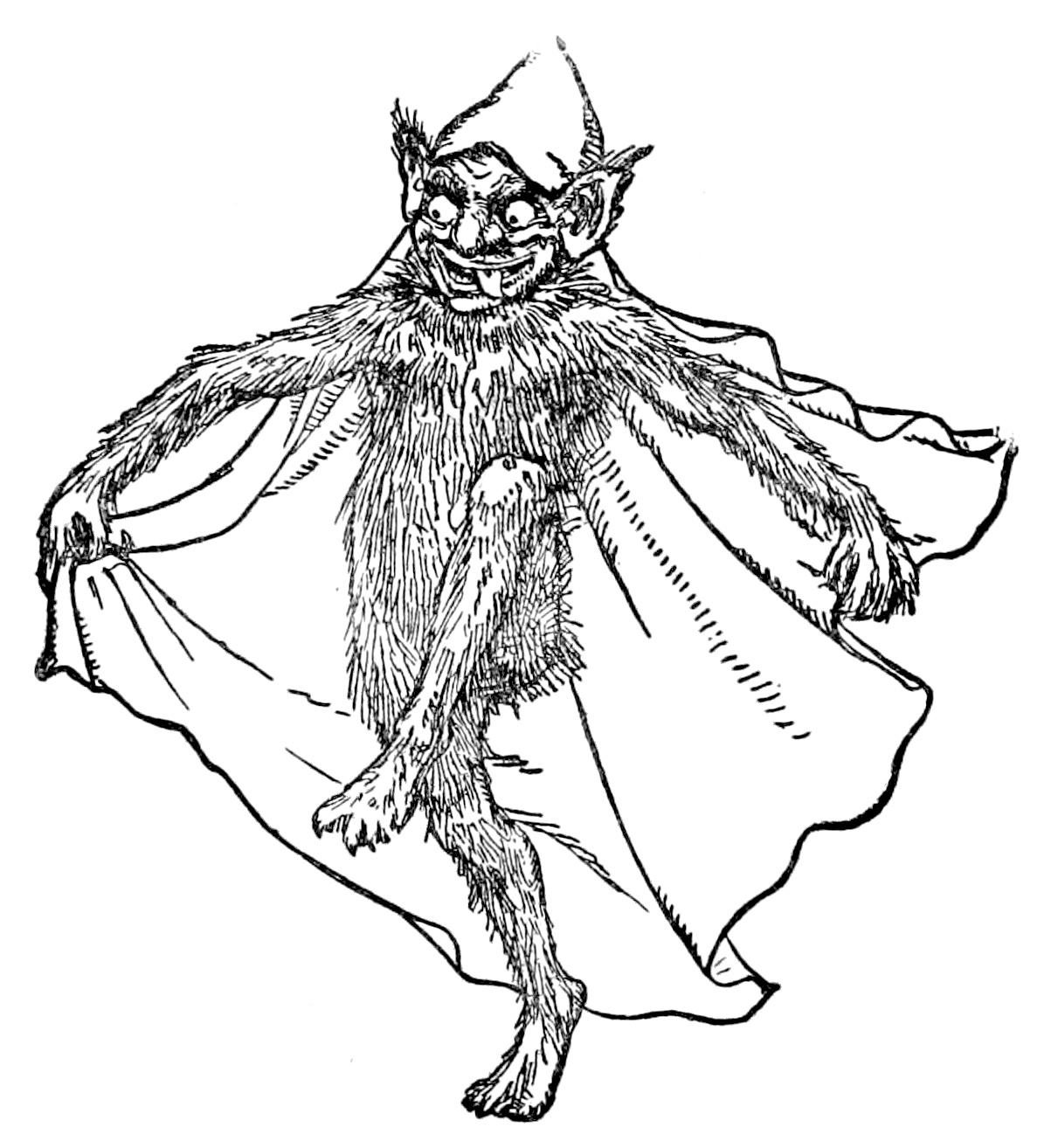

In short, good goblins are the epitome of the “weird little mud freak” as Brad Kerr frequently mentions on the Between Two Cairns podcast. They’re weird little guys who like living in the dungeon and will not be normal about it. But actually nailing that vibe is a bit more complicated.

The biggest problem with goblins in a TTRPG is that they’re easily slotted in as vicious little evil dudes your players shouldn’t feel bad about slaughtering. I certainly did this in my first campaign as a GM running Pathfinder. Goblins were everywhere on the overland encounter table, always ready to pop out of a hole and cause problems, but not really serving a purpose other than to provide a quick fight. They were just there as nasty minions of evil.

While there’s an argument for the need for that kind of enemy in a combat-focused game, goblins can be so much more than that. The key to understanding how to really make them work is to remember that the origin of goblins is as a variety of fey creatures covering the spectrum of impish tricksters to murderous thieves. Yes, they’re capable of great violence, but they’re also complicated, and a big part of what makes them scary is that humans have a hard time understanding their motivations and organization. Yes, many of them would gladly eat you alive, but there are rules about how and when that’s appropriate.

I think there’s no better example than going back to Tolkien with the Hobbit, which is arguably the avenue through which the modern conception of goblins in D&D came. When the goblins capture the party in the Misty Mountains they don’t attack them immediately, they capture them to take them to a king. Goblins aren’t a disorganized rabble of bloodthirsty monsters, they’re a perversion of human society mimicking the structures of it on top of the bloodthirstiness that’s also there. The goblins want to kill, and probably eat, the dwarves, but they need to talk to them first and justify why they’re in the right for killing them as a redress for past wrongs against them. Of course that all eventually breaks down into chaos and violence, but the pretense of order before that enriches that part of the story and makes the goblins more interesting as characters.

My personal favorite depiction of goblins is in the semi-farcical fantasy novel One For the Morning Glory. In that book, the goblins live directly under the human city, accessible by the sewers, and they’ve been holding a human woman captive for years. They have a court with structure and nobility, and their own sense of aesthetics, wearing mismatched clothes sewn directly into their skin with cutouts for oozing wounds and scars. They’re gross and weird, but they have a logic to them and, again, a perverse reflection of the order of human society. In the dramatic climax to the sequence in the goblin tunnels, they play out a version of the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, with the heros not able to look back as they walk out with the captured woman behind them. All the while, the goblins mimic her voice, trying to get them to turn around so they’re be justified in killing them. It again breaks down into chaos and violence in the end, but there’s a structure to it, a weirdness of how the violence plays out that elevates it beyond fighting low level minions.

I tried to capture some of this in my own work with the swampkins in A Tomb of Twins, adding a set of more complex swampkin NPCs for the players to interact with. But, I’ll readily admit I don’t think I really got there with it in that case, and goblins can be done a lot better by focusing on the fey weirdness of them paired with the violence inherent to them.